A multimillion-dollar grant from the National Institutes of Health will fund research at UC Merced that could help cancer patients and others live longer, healthier lives.

The $3.5 million, five-year grant will fund bioengineering Professor Joel Spencer's lab, which is investigating the thymus, a key organ in the human immune system.

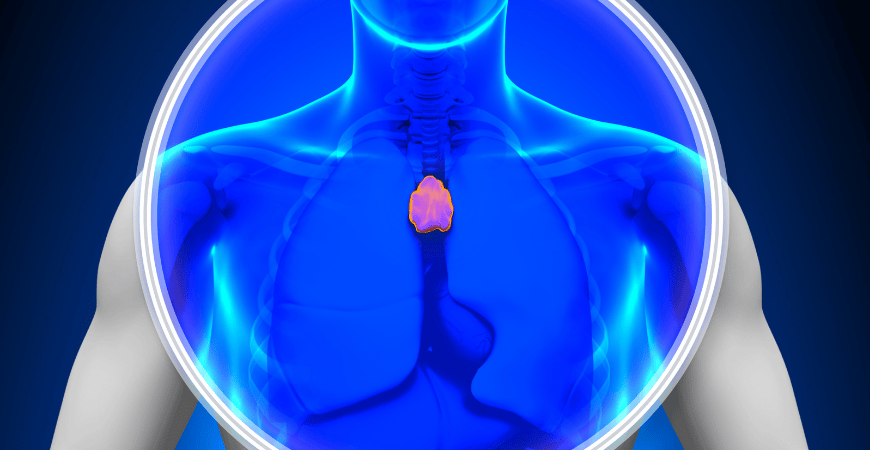

The thymus, located under the sternum and on top of the heart, is where a type of white blood cell called a T cell develops. T cells originate from stem cells in the bone marrow and help protect the body from infection. The thymus has recently been shown to be important for maintaining health throughout life.

"What's interesting about the thymus is it gets its heyday in your youth," said Spencer, a member of the university's Health Sciences Research Institute. After that, "it starts to shrink, and function starts to diminish so by the time you're in your early 20s it looks old."

And some treatments, such as chemotherapy or radiation, can damage the thymus as well as bone marrow while killing unhealthy cells such as cancer.

"If you damage the bone marrow it needs to be repaired," Spencer said. "One of the first things we're trying to do clinically is restore normal blood cells in your bone marrow."

But the impacts on the thymus are not as well understood.

The research funded by the grant, Spencer said in his proposal, "will hopefully enable us to make an impact in our understanding of how a key organ in our immune system (the thymus) responds to acute damage and open up potential therapeutic targets for regenerating the thymus and immune system after damage or aging."

The research funded by the grant, Spencer said in his proposal, "will hopefully enable us to make an impact in our understanding of how a key organ in our immune system (the thymus) responds to acute damage and open up potential therapeutic targets for regenerating the thymus and immune system after damage or aging."

Spencer's lab will use a novel imaging system it developed to focus on endothelial cells, which make up blood vessels and interact with other cells in the thymus.

Spencer likened blood vessels to highways.

"If there's a car accident on one of the highways, you're going to get traffic for miles," he said. "We know that these highways, these blood vessels, are also impacted by cancer treatments. We can see the structure of those highways and we want to study how that might play a role in regeneration."

To accomplish that, the lab will use cutting-edge technology that it developed to examine the thymus of mice. Previously, researchers had to transplant the thymus somewhere else to examine it due to its location in the body.

"But you completely alter the blood system when you disconnect it," he said.

Other researchers have used zebrafish because their organs are more easily examined. But fish and mammals have key immunological differences, so it's more difficult to translate that data.

Spencer credited the members in his lab, particularly graduate student Christian S. Burns and previous graduate student Negar Tehrani, with having the tenacity needed to develop the imaging tool. Tehrani has since completed her doctorate. Spencer also credited previous graduate student Nastaran Abbasizadeh and undergraduate researchers Ruth Verrinder and Victoria Okafor for their role in this work. Researchers published a paper about the new thymus imaging technology in the journal PLOS One.

"We had a lot of trial and error," he said. "We tried hard and failed, for probably four to five years. When we finally got our first images of the thymus and could see blood flow, it was a huge accomplishment."

Spencer said the grant from NIH will allow the lab to take its work to the next level and gain greater insight into both how the thymus works and how its function might be protected.

"It's opening up a lot of possibilities for what we're going to do."

Public Information Officer

Public Information Officer