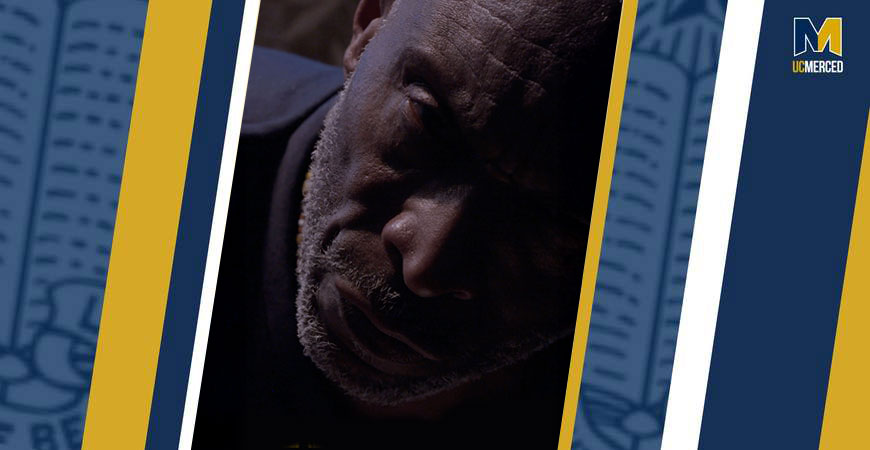

A UC Merced professor entered the bleak world of a fading, 64-year-old man in a Virginia state prison to illustrate the challenges of being elderly and incarcerated.

“Where’s My Coffee Cup?” is a half-hour documentary by media and performance studies Professor Yehuda Sharim. It premieres April 18 at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture. Plans are underway to present the film worldwide, including a possible screening at UC Merced this fall.

According to the documentary, John, the film’s central figure, has been behind bars for 33 years “in a space not designed for a geriatric population. He faces the challenges of stairs, top bunk and the constant risk for violence and exploitation.”

Sharim said the film is the first of three planned with incarcerated people in Virginia. He has worked for the past three years with the Coalition for Justice, a prisoner advocacy group based in the state. (Sharim and Coalition for Justice's Margaret Breslau were interviewed about the film by Virginia public radio station WVTF.)

Supporters of the project include the Henry Luce Foundation and UC Merced’s Center for the Humanities.

“This trilogy is the story of our society — what we don't want to see, who we don't want to hear, our obsession with punishment, and carceral genocide in our midst,” Sharim said.

In a review of the documentary, Professor Tanya Golash-Boza, executive director of the University of California in Washington, D.C., said it “puts a face on the lasting consequences of policy decisions made in the late 20th century, when the United States embarked on an experiment of addressing crime through mass incarceration. Sharim’s film shines a light on the indignities faced by an aging prison population and helps us to reckon with an often-hidden aspect of our criminal legal system.”

UC Merced literature Professor Nigel Hatton wrote in a review that “Where’s My Coffee Cup?” exposes the Virginia prison system’s “absence of care and the accumulation of physical injury and loss for aging human beings wasting away in what are effectively waiting-to-die warehouses.”

Hatton added: “This film amplifies the cries of captive poetic and disheartened voices — ‘If more people knew what goes on in here, they may care more.’”

Public Information Officer

Public Information Officer