It was, depending on who’s talking, a tumble into the deep end. A triage driven by exhaustive planning and exhausting, sleep-deprived days. A severing from the face-to-face culture that energizes teachers and learners.

In just over three weeks, more than 10,000 UC Merced students, faculty and staff were forced off campus by the novel coronavirus outbreak. By the end of March, when instruction resumed after spring break, the immersion was complete. Staff, faculty and students came face-to-laptop with applications designed to connect, organize and sustain from a distance: Kaltura, SpeedGrader and Respondus; Slack, Teams and Airtable. And Zoom. So much Zoom.

As the weeks have turned to months and California and UC leaders watch the data for signs it’s safe to come together again, think on this: How much of this compressed exposure to digital tools will follow the campus community into a post-pandemic world?

“This has given everyone on campus a lived experience of the potential advantages technology gives us,” said university Chief Information Officer Ann Kovalchick, who worked at Tulane University when Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005. “Sometimes you have to learn how to tame technology. It just means you have to play with it a little bit.”

The university will have some tools it didn’t have before. An example: In mid-March, students and faculty learned they needed remote access to special software on lab computers. Rachel Peters, Learning Technologies manager in the Office of Information Technology (OIT), beat the bushes and found a possible solution online. But the open-source code from the University of Syracuse needed serious updating. Peters and an OIT team dove in.

“We got a working service that was mostly reliable in a week,” she said. “I can’t believe we pulled it off.”

Weeks earlier, OIT staff began building out a webpage that described software faculty could use for remote instruction, and when and how to use them. Peters approached Kovalchick about posting the content in late February. The first iteration of the page went up March 4 – two weeks before Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered all Californians to shelter in place.

“We were all seeing the writing on the wall,” said Jodon Bellofatto, OIT lead analyst for Technology Enhanced Spaces. “There was so much inertia toward shutting down (the campus), then the governor decreed it.”

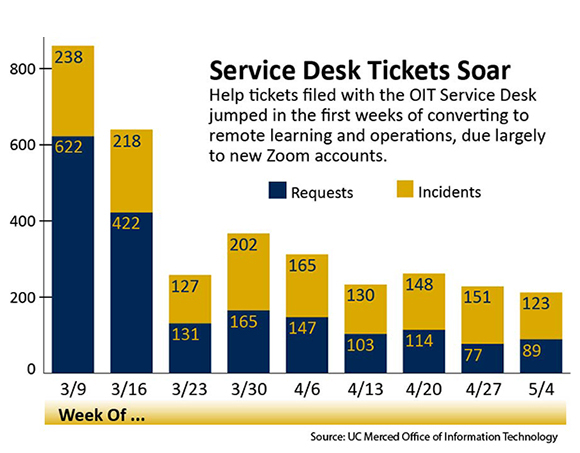

OIT has a similar webpage devoted to Zoom, the online meeting tool that seemingly overnight became the campus community’s proxy for in-person contact. Before the health crisis, there only were a few hundred staff or faculty members with Zoom licenses. Normally, OIT would order licenses in batches of 100 or 200. When the crisis arrived and campus leadership determined students needed Zoom, too, OIT secured a campus-wide license in late March. That meant anyone with a university Single Sign-On account had access to the full capabilities of the application. Eventually, about 9,700 users were added.

“We knew the campus was going to move to remote instruction,” said Edson Gonzales, OIT videoconferencing and media streaming specialist. “It was all hands on deck. I pretty much didn’t sleep for two or three weeks because there was so much going on.”

The webpage will remain after the pandemic is over, as will an OIT newsletter launched in April. Information Officer Christy Snyder said the pandemic changed how OIT communicates with the campus about technology.

“We’re much more purposeful,” she said. “More broadly, it’s made us a better partner.”

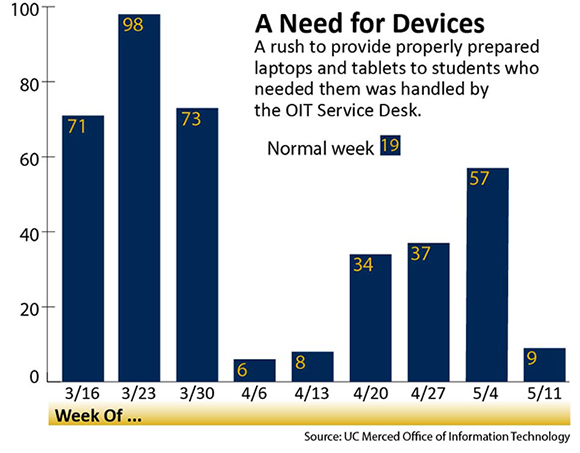

OIT’s Service Desk team was at the center of the transformation, handling huge spikes in service tickets and taking over an empty classroom to spread out laptops that would be prepared for students’ use. Two team members stayed on campus while the remaining six switched to remote work.

Director of Service Management Kent Carpenter said he and Service Desk Manager Alex Hernandez-Perez mapped scenarios of how the campus might respond to the pandemic. By the week of March 8, “it became very clear what was going to happen,” Carpenter said.

But the swift shift to remote didn’t just expose the campus community to unfamiliar technology. Student surveys, task force investigations and anecdotal evidence have shown a decrease in satisfaction and motivation among faculty and students “that before the COVID crisis would have been hard to quantify,” interim Vice Provost and Dean for Graduate Education James Zimmerman said.

When you remove people from others who also are motivated to pursue intellectual goals, there appears to be a loss of energy and drive, said Zimmerman, who co-leads a faculty group monitoring instructional resilience during the pandemic. On the other hand, this experience should help encourage faculty to use more digital tools, such as recording lectures that students can use for review, he said.

Zimmerman, an experimental nuclear chemist, noted that the UC Office of the President offers a grant that encourages faculty to develop hybrid and online courses. A couple years ago, about 10 UC Merced instructors started using the funding.

“When COVID hit, the challenge was to hasten that process for the other 95 percent of the faculty,” Zimmerman said, adding that hybrid courses are typically a much better fit for UC Merced students than fully online classes.

The university’s research mission is another matter.

“There are few things a researcher can do when he or she is removed from their lab,” Zimmerman said. Two of those few things are computer simulation and data computation, if the type of research allows for them.

Which is why it was crucial to activate the Borg Cube even as the campus shuttered around it.

"Sometimes you have to learn how to tame technology. It just means you have to play with it a little bit."

In the early morning of March 17, the $1.5 million high-performance computing cluster (HPC) in Science and Engineering 2 began a move to a new home — a temperature-controlled steel box of a building officially called the Computational Research Facility, but better known at OIT by its “Star Trek” nickname, the Borg Cube.

Two days into the move, Newson announced the statewide shelter-in-place order. Professors Hrant Hratchian and Suzanne Sindi, co-directors of OIT’s Cyberinfrastructure and Research Technologies unit, spent hours texting each other about whether the HPC move could proceed.

“We didn’t know if we were going to get this done,” said Sindi, a professor of applied mathematics who gave the new facility its sci-fi moniker.

But they pulled it off with HPC Manager Sarvani Chadalapaka directing the move team on the ground, managing as others provided coordination remotely. The computing cluster's roomier home allowed OIT to boost its computational capacity by 50 percent, Chadalapaka said.

Hratchian, a chemistry professor, said some campus researchers, restricted by inaccessibility to their labs, are using the HPC for whatever computations they can do now.

“It’s the one research operation that’s open for business,” he said.

How much will more powerful research computing, along with exposure to other high-tech tools — and the new instructions to use them — be used after the university returns to whatever is defined as normal? Like the virus that triggered the exposure, the outcome is uncertain.

“Will there be an uptick in the use of these tools? Certainly,” Zimmerman said. “A small one.”

Sindi, amid a discussion about possible expansion of computational research, might as well have been speaking to the larger question when she said: “I think some of it is going to be very purposeful pivoting, and some of it will need to happen more naturally.”