California’s drought was hard not to notice — the dry lawns, fallowed fields and hot temperatures were evident across the state. To better understand how the drought affected the natural ecosystem in which we live, biology Professor Jason Sexton and his graduate students conducted a study on a California plant known only from the Sierra Nevada — the cut-leaf monkey flower.

Sexton, a botanist by trade, studies plant adaptation affected by major ecological changes. To study the influence of the most recent drought that lasted roughly from 2011-2017, Sexton drew upon his seed collection, which he started during his graduate work at UC Davis. Among his gatherings were seeds from the cut-leaf monkey flower plant, which he started collecting in 2005.

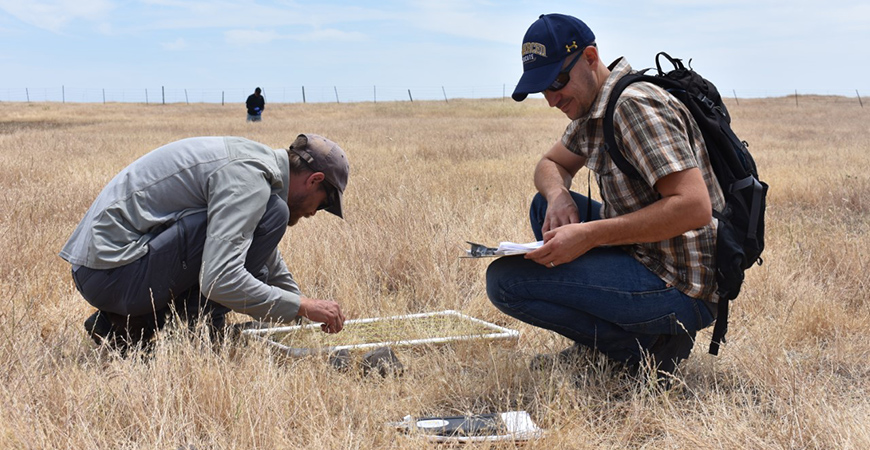

Two graduate students in Sexton’s lab, Lillie Pennington and Erin Dickman, conducted a resurrection study in which they compared the pre-drought seed growth to the drought-generation monkey flower seeds collected in 2014.

“There is a background level of change that’s always happening, and we want to compare that to a narrative of natural selection or adaptation,” Sexton said. “The idea behind it really comes down to understanding what happens to populations when we have a major ecological event, like the drought.”

To better understand this, Sexton and his graduate students planted pre-drought generation seeds from 2005 adjacent to drought generation seeds to observe their traits and changes. The result?

“The drought-generation plants emerged and flowered earlier, as well as achieved a bigger size,” Sexton said. “They got larger and produced more seeds, so that was evidence that they had adapted to the drought.”

Dryer conditions, like a drought, favor fast-emerging seeds, so slower-emerging seeds did not persist into the next generation in the study. The experiment also revealed a reduction in the range of seed emergence time during the drought, meaning a potential loss of genetic variation.

“I think it is an important study, especially now in this era of rapid climactic change when we don’t really know how native plants are responding to the change,” Pennington said.

Pennington continues to work with the monkey flower, and the rest of her research focuses on imposing drought conditions on both pre-drought and drought generations of the monkey flower to see which perform better. This also includes examining seeds from not just different environmental conditions, but also from different elevations.

“The lower-elevation populations already experience warmer conditions than usual, so when the drought happened, the change in precipitation and temperature wasn’t as extreme,” Pennington explained. “Higher and central populations potentially experienced a more pronounced change in temperature and precipitation.”

Genetic variation is not limitless, so Pennington aims to determine if the monkey flower has lost genetic variation, or if it will come back.

Moving forward, Sexton said, his concern is the severity of future droughts, which are predicted to happen again. This reduction in water, coupled with the reduction in snowpack, means there could be long-lasting effects on native plant species.

“When we study what is happening in the natural world right now, with no human influence, you can go out and see what nature is doing with global change,” Sexton said. “Studying climactic events like this gives us a sense of what nature might do in response in the future.”