Cancer is vicious. In 2025, it is expected to cause more than 618,000 U.S. deaths — nearly twice the combined populations of Merced and Modesto. Each year, almost half of this nation, young and old, is touched by the disease through personal diagnosis or an afflicted loved one.

Jeff Yoshimi joined the 50% when his wife, Sandy, learned she had breast cancer. The blighted cells had spread to some lymph nodes.

Alongside Sandy during one of many overnight hospital stays, Yoshimi drifted in and out of sleep, sifting through ideas drawn from his profession and passions: a Ph.D. in philosophy, research into how people perceive and experience the world and expertise with clarifying tough-to-grasp concepts by visualizing them in game-like ways.

How could he, a UC Merced cognitive science professor, take the fight to a horrible disease?

Suddenly, the pieces in his head snapped into place. Yoshimi grabbed his laptop, went across the street to an all-night coffee shop and began to type. Cancer, he knew, can be curable, but it takes so many forms and changes guises so often that it is incredibly tough to fend off. But what if the brainpower available to cancer research was increased exponentially? What if that power came from millions of minds that love to unravel mysteries, mash buttons and obliterate bad guys?

What if, Yoshimi thought, we scaled up the cancer battle with a suite of truly awesome video games? From that first flash in 2013 and over 11 years, he expanded the idea into a compelling action plan and put it in a book. “Gaming Cancer,” published by MIT Press. In it, he asserts that gamified citizen science, teamed with the soaring potential of artificial intelligence, can help power significant advances in cancer research.

Sandy Yoshimi is alive and well today after enduring a grueling journey of surgery, chemo, radiation and pills. Cancer, however, was not done with the family. Sandy Yoshimi’s sister died from colon cancer not long after Jeff Yoshimi started writing the book. In 2023, bile duct cancer took the life of Sandy’s father.

“Much of this book was written in cancer wards and chemo rooms,” Yoshimi says in the first chapter.

The book’s subtitle describes the goal: “How Building and Playing Video Games Can Accelerate Scientific Discovery.” With a breezy writing style, Yoshimi walks readers through not just how it can be done but why it should be done.

“Scientific problems associated with cancer are messy and complex,” he wrote, “but in some cases they have core logic that can be presented in a game context with its simplified rules.”

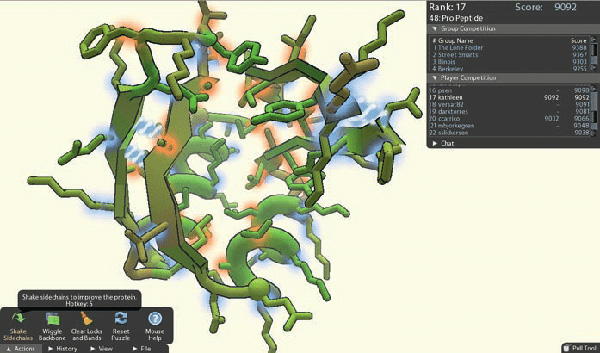

Citizen science games are out there, though on a far smaller scale than what Yoshimi lays out in the book. One example: “Foldit” makes a video game out of how proteins restructure themselves. Outcomes from this “protein folding” game can help scientists understand cellular mutation and runaway replication of diseased tissue. It can help perfect therapeutic drugs.

In 2020, about 750,000 users played “Foldit.” An impressive number, but Yoshimi is thinking bigger. Like “Baldur’s Gate” bigger. “Candy Crush” bigger.

Yoshimi has hands-on experience with game-style programs. In 2008 he created Simbrain, where users design neural networks with simplified visuals. He uses Simbrain in his courses and research, helping students and colleagues grasp aspects of neuroscience, psychology and artificial intelligence.

In an interview, Yoshimi, a UC Merced founding faculty member who came aboard in 2004, talked about the knowledge that could be unleashed by scaling up citizen science. He told a story about going to a restaurant with his father and seeing a boy whose knee bounced like a jackhammer.

“My dad said, ‘I wonder if we could make a little generator, attach it to that knee and capture all that energy,’” Yoshimi said.

“That stuck with me. People have these exquisitely evolved brains and we enjoy solving puzzles. It’s good for the species. So we have this huge reservoir of untapped problem-solving power, this Earth-wide computing effort being used on ‘Grand Theft Auto.’

“What if we redirected some of that to problems of broad significance, like cancer?”

In the book, Yoshimi discusses the “meta-game” — the process of creating this suite of powerful, irresistible games. He details everything they need: crack programmers, visionary leaders and deep-pocketed financiers, as well as reward structures for users and smooth links between gamers and labs. At the center of it all Yoshimi envisions Simbody, a game engine that simulates biological systems from whole bodies to nanoscale.

Start with a cancer conundrum. Break down the problem until there’s one task a game could tackle. Plug it in. Yoshimi said the suite, which he dubbed “Cancer Wars,” could use all the game styles: action, adventure, role-playing, first-person shooter, strategy, sports.

Only a couple years ago, artificial intelligence, which Yoshimi has studied for years, punched the turbos with the arrival of large language models such as ChatGPT. Suddenly, it seemed AI was going to change the game. Why turn to people for crowdsourcing when LLMs have trillions of bits of information crowded into their silicon brains?

Actually, why not do both?

Yoshimi said many of the existing citizen science games have AI elements that work hand-in-hand with the player, matching the former’s data-processing power with the latter’s power of intuition.

“We want to have human-AI symbiosis,” he said. “AI can do raw number crunching and statistical generalization. Humans see the bigger picture, the relevance of one thing to another, the creative insight that a machine finds harder to capture.”

Think Capt. Picard and Data, Yoshimi said. Luke Skywalker and C3PO. Kirk and Spock.

“AI has made big jumps, but it’s not at a point where we push a button, ChatGPT thinks about it for a month and solves the problem,” he said. “The best games will take AI as far as it can go, interweaved with human intelligence, so the experience is seamless.”

Yoshimi hopes “Gaming Cancer” offers a roadmap for ramping up video games in the fight against cancer. He added that eradicating the disease is a worthy goal but certainly not the only one. There are countless important victories within reach. Detection and treatments for the hundreds of cancer types demand attention. Games can foster an understanding of clinical research and promote lifestyle choices that can reduce cancer risk.

Because this is cancer we’re talking about. Only heart disease kills more Americans. Why not bring a legion of video gamers into the battle?

“It’s worth the effort,” Yoshimi said. “Even if you don’t hit the moon shot, all the intermediate shots are valuable.”

Public Information Officer

Public Information Officer