California counties with high numbers of low-wage workers are seeing higher incidence of COVID-19, suggesting a link between so-called “worker distress” and spread of the virus, according to a new study by UC Merced’s Community and Labor Center.

While efforts to contain COVID-19 have centered on regulating large gatherings and closing certain businesses, the findings suggest authorities must also track transmissions within low-wage industries and create a greater safety net for workers in essential jobs.

“COVID-19 may travel through tightly congested work environments or overcrowded housing,” said the study’s authors, sociology Professor Edward Orozco Flores and Community and Labor Center Executive Director Ana Padilla.

“In turn, the lack of options available to low-wage, essential workers to cope with the pandemic — as many lack access to unemployment benefits, emergency paid sick or family leave or health insurance — places low-wage workers and their communities at higher risk of COVID-19 infection and transmission.”

The study of data from California’s 58 counties and the U.S. Census Bureau found a strong relationship between low-wage work and COVID-19 positive test rates. It also identified industries with the greatest prevalence of low wages, such as agricultural work, food services, transportation and other essential roles.

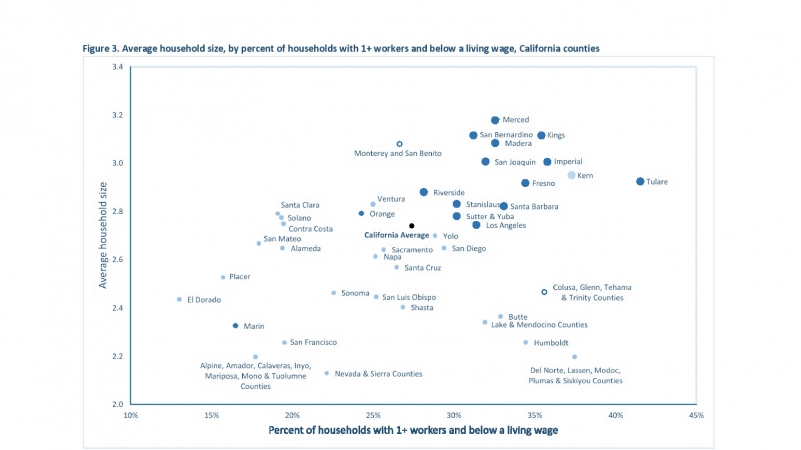

Analysts examined worker distress by considering the percentage of households living below a living wage and the number of people in a household. Fifteen counties that surpassed state averages for both measures were deemed to be high in worker distress.

The counties include seven in the San Joaquin Valley: Tulare, Kern, Kings, Fresno, Madera, Merced and Stanislaus. Others were San Joaquin, Sutter and Yuba in Northern California; and Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Bernardino, Riverside and Imperial in Southern California.

Nearly all of the counties with high worker distress are on the state watchlist for those with COVID-19 positivity rates above 8 percent. In comparison, only two of the 37 counties with low worker distress were above that threshold.

The relationship between worker distress and COVID-19 positivity held constant across rural, suburban and urban regions, the study found.

Low-wage workers and their communities have been put at higher risk of virus exposure, with Blacks and Latinos suffering the highest rates of infection and death. And people who must work due to a lack of unemployment benefits, emergency leave or health insurance place themselves and their families and neighbors at increased risk.

The study’s authors recommend that COVID-19 positivity rates be tracked by industry to help develop workplace health and safety standards that could counter the virus’ spread. The broader public will be made safer through efforts to reform workplace health and safety and to give workers greater access to unemployment benefits, health care and paid leave, it said.

Padilla and Flores were invited to present their findings at the July 16 meeting of the state Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board. The body began steps to act on the findings within the next year.

“Our findings indicate low-wage work is associated with the spread of COVID-19, and that to mitigate COVID-19 spread it is not enough to simply regulate business openings and public gatherings,” the authors said. “Policymakers must also innovate health and safety reforms focused on the workplace and provide a greater safety net for workers.”