The following article is the main story in a six-piece package that appeared in the spring issue of UC Merced Magazine focusing on the research performed at UC Merced that relates to the brain. You can read the other stories, on consciousness, machine learning and artificial intelligence, linguistics, developmental psychology and the study of brain elasticity online.

The very idea of a purple zebra is odd — outside reality as we know it.

But it is not beyond the capability of our minds to imagine and picture such a mythical creature.

The human brain can take two disparate concepts in our memories and connect and combine them in milliseconds. The speed and smoothness are so remarkable that even a supercomputer — if it had emotions — would be jealous.

The interaction of brain biology and lifelong personal experience has compelling scientific as well as social implications. That mixture fascinates researchers in UC Merced's Cognitive and Information Sciences (CIS) program.

In fact, it forms the basis of much of their work. And as a result of their varied interests and projects, the campus has emerged as a nationally well-regarded center of research about the brain and cognition.

Merced scholars are investigating how the mind operates in the world and how we should approach — excuse the pun — the heady task of thinking about thinking.

So how does a purple zebra work?

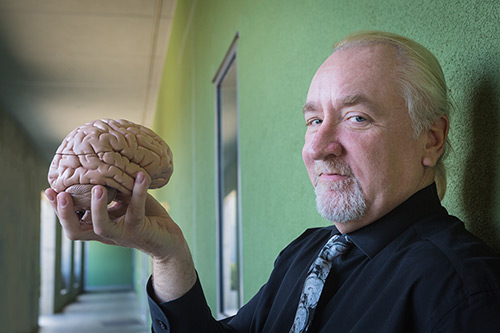

Neural pathways in the prefrontal cortex signal circuits further back in the brain, tap the knowledge stored there and combine chunks of information efficiently, said Professor David Noelle, who studies such brain functions and constructs computer simulations of them.

The brain “very flexibly recombines parts of old ideas to create new ideas,” Noelle explained. His research focuses in part on how neurons within stripes of tissues in the prefrontal cortex “mutually excite each other” and “talk to each other.” Information about “purpleness” and “zebraness” appear throughout the brain but signals from the prefrontal cortex “bind” them together so we can entertain a novel idea.

But the ability to do that, Noelle emphasized, depends on reusing and combining parts of past learning and experiences.

So a stunted childhood without an enriching learning environment could cause problems later on; it might be difficult for such an adult to be creative, to comprehend new situations and to adjust behavior to match changing circumstances, he said.

New Approach to the Brain

Noelle and a dozen of his colleagues are part of a tradition that dates back to ancient philosophers theorizing about the soul. However, today's faculty researchers work in a 21st-century scientific universe of brain scans, genetic engineering and artificial intelligence.

Without a medical school and hospital to provide an immediate entrée to clinical research, UC Merced decided from its founding not to compete with such neuroscience powerhouses as UC San Diego; instead, university pioneers opted for a more computational emphasis in brain research and an interdisciplinary format, with a lot of connections to computer science and engineering.

And the program is anchored in the somewhat contrarian ethos that the mind arises from more than just the physical organ of the brain — it also critically depends on the rest of the body, the outer world and possibly even other people.

Free of the traditional departmental constraints at older schools, the UC system's newest campus has brought together philosophers, linguistics experts, artificial intelligence engineers, psychologists, neuroscientists and others under a big and porous tent. Another dozen or so faculty outside the CIS program also participate in the work.

Their overall collaboration and communication promise to create some new ideas, not unlike a purple zebra.

Teenie Matlock, a cognitive science professor who was hired in 2004 to found the program, said its interdisciplinary nature sets Merced's brain and mind research apart from that at other campuses.

It allows faculty members to tackle “real-world problems without losing the elegance of the theory. For us, applied work is not a dirty word,” said Matlock.

Her own research looks at language and reasoning, especially how subtle shifts in wording can dramatically affect people’s attitudes toward political candidates, climate change and other issues, said Matlock, who holds the McClatchy Chair in Communications at UC Merced.

“We already know that language influences thinking and behavior,” she explained. “The deeper and more interesting questions — and where we need to learn much more — relate to how language influences us across different situations and over different time scales.” Matlock also noted the importance of examining those linguistic effects “across different cultures and age groups.”

Along that line, professors Anne Warlaumont and Stephanie Shih study speech processing at different ages and in different languages.

The Philosophy of the Brain

Some of the brain research and writing at UC Merced has a distinctly philosophical rather than medical flavor.

Professors and students debate thorny questions of consciousness — what constitutes volition and real thinking and what just is the result of the electrical impulses among the brain's 100 billion neurons?

Yet even those projects could have implications for such varied and pressing issues as autism, computer design, the language of political engagement, criminal behavior, voice activation on cell phones and how to keep the elderly intellectually sharp.

Yet even those projects could have implications for such varied and pressing issues as autism, computer design, the language of political engagement, criminal behavior, voice activation on cell phones and how to keep the elderly intellectually sharp.

For example, Professor Jeffrey Yoshimi's research about “neurophenomenology” probes the relationship between conscious experience and the brain's functions.

Yoshimi has developed a computer program, with strong visual and video components, that simulates and manipulates such brain functions as object recognition. Snip connections in a faux neural pathway and a robot — or person — may no longer be able to tell a fish from a hunk of cheese.

Research in this area could eventually deepen understanding of many aspects of the mind, including human brain injuries and schizophrenia, Yoshimi said.

“When my undergrad advisors in philosophy told me that computers can't think, my response was, ‘Maybe not, but we can certainly use computers to study the brain, and the brain thinks,’” he said.

Fellow researcher Noelle said he hopes his research might lead to the development of mental exercises that help maintain the brain's ability to make connections and be creative in old age. While “brain games” like those offered by Lumosity have recently been critiqued as lacking scientific support, other possibilities have yet to be explored for maintaining and improving flexibility of thought, he said.

At another point of life, new mental exercises might help teens compensate for the fact that their frontal brain systems are not fully developed and help them “improve their general ability to stay focused on what they should be doing right now,” Noelle added.

Human and Other Intelligences

Some professors work more directly with human subjects.

Professor Ramesh Balasubramaniam is investigating aspects of balance, the perception of rhythm and beat and how the nervous system works to move several body parts at the same time. With technology called transcranial magnetic stimulation, he induces temporary changes in human brain functions, exciting or slowing neurons for brief periods.

Professor Rick Dale and his collaborators study interpersonal communication and body language as people try to understand each other, lie to each other and make decisions. His “Cognaction” Laboratory has started to use Google Glass as a tool to study interaction and has participated in massive surveys about the use of Twitter.

Professor Paul Maglio works on human-computer interfaces and the human aspects of autonomic computing, among other cognitive science research.

Professor Michael Spivey tracks eye movements of volunteers in response to changing visual and auditory information on a computer. He tests how the duration and sequence of data can affect human choices, including such large moral questions as whether homicide can ever be justified.

Spivey's work also has implications for building robots to better recognize and react to objects in the physical world.

Spivey and many other UC Merced cognitive science faculty members share a perspective called “embodied cognition.”

Under that framework, the mind encompasses more than just the brain and includes “the relationship between the brain and the body and how that body interacts with the environment,” Spivey said. The mind can expand to a shared consciousness that includes two or more people working together closely on the same task, romantic partners in a loving conversation and even to interacting with pets.

And yes, A.I. geeks, it could include a working relationship with an intelligent robot.

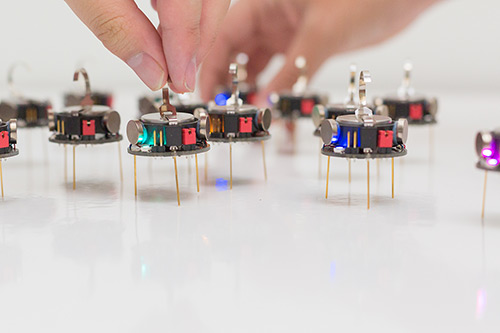

Professor Christopher Kello is working on building future computer technologies so that they are “more like people in how they are smart and less like traditional computers.”

The cognitive mechanics lab he runs on campus investigates reading, speech and search functions; he and his graduate students are creating simulations of brain functions that could lead to the design of more powerful, efficient and brain-like computer chips.

Computers are now better than most humans — except for some savants — at “storing vast amounts of bits and bytes and accessing those very quickly,” he said.

But brains are much more efficient overall in terms of size and energy consumption, Kello explained.

Plus, he said, brains are so much better at multi-tasking, understanding simultaneously “what my feet are feeling, what my skin is feeling, what I am hearing, what I am seeing.”

One of Kello’s current projects, with a grant from Google, is to improve the capabilities of computerized speech, such as the speech interpretation and recognition interface used in smartphones.

The goal is a better Siri, in effect.

“It would be really wonderful if Siri had a voice that could be naturally manipulated to be young or old, have a British or a New York accent. That would be kind of cool,” Kello said. But first, we need “a better and deeper understanding” about how to replicate voices on a computer, Kello said.

Another path of his research involves how the brain self-regulates its activities, how its neurons send signals to each other. A healthy human brain follows the so-called Goldilocks approach to porridge heat: producing just the right amount of signals, not too many and not too few. That self-regulation leads to better thinking, better memory, better perceptions and better abilities to perform tasks. Too much activity or too little is linked to such impairments as epilepsy.

Bigger Than the Brain

Philosophers and theologians talk about a spirit or soul that might have existed even before the body it currently inhabits, and which lives on separately after that body dies.

Some modern scientists instead place the biological brain on an exalted level, ascribing all human thought and behavior to neural and chemical surges without any spirituality attached.

Others of a more religious bent, however, speculate that the soul is something independent of the brain and is essentially beyond the reach of such modern tools as scans and neurosurgery.

Cognitive science classes at UC Merced still discuss those “mind-body” questions and traditions. But they frequently go one step further.

Professor Carolyn Dicey Jennings, who teaches philosophy and cognitive science in the CIS program, said the extra step is describing how the mind works “dynamically” with the world.

For example, when a person plays a piano, the neurons and the nervous system are part of the experience, but so are the muscles, the entire body and the piano itself, along with the history of the kind of piano the musician learned to play on, she explained.

In this perspective, “the mind is partially made up of the things you are engaging with,” Jennings said.

So while the long-range impact of humans becoming so connected to their iPhones and laptops is not fully known, there surely will be some effect.

“If most of your life is spent behind a screen, you will have a different mind than if you did not spend all that time behind your screen,” Jennings said.

The bottom line, she said, is that the mind “is not just the brain. It is bigger.”

Lorena Anderson

Senior Writer and Public Information Representative

Office: (209) 228-4406

Mobile: (209) 201-6255